Holed up in Side Room One, I knew for sure that I was dying. I was marble white, confused to the point of delirium, and for the life of me, I couldn’t catch a breath. For two days, I’d been berating my partner and mother for things they hadn’t done, and frequently became convinced the tubes, lines, and wires attached to me were conspiring to wrap around my body and crush me like a python. Irrational? I know. Red flags? So many.

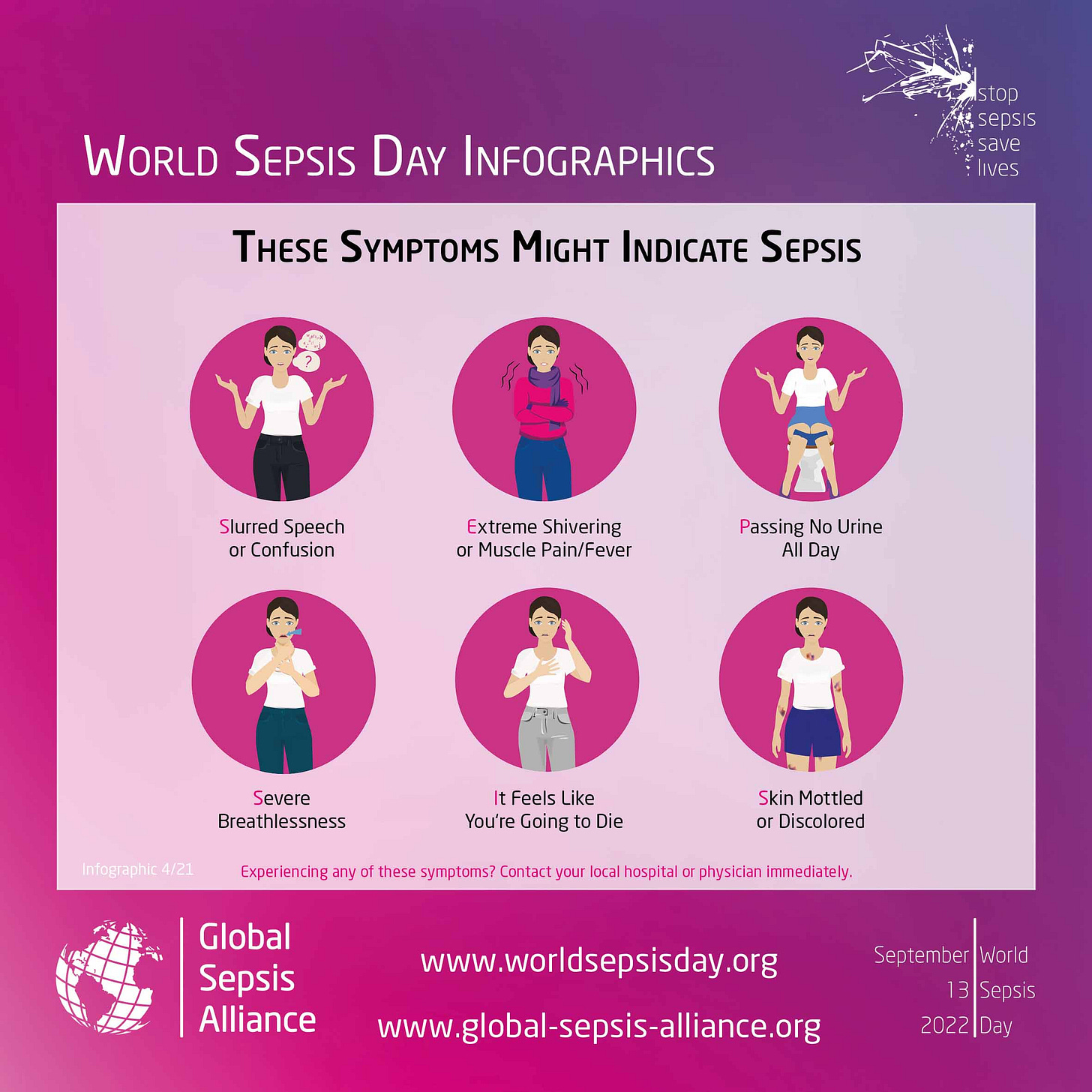

These are just some of the signs that may indicate sepsis. But during a prolonged hospital admission in 2018, I wasn’t aware of the symptoms, and apparently, neither was the on-call doctor.

By the time the nurses sent for him, it was late at night, and I was balled up on my bed screaming – very out of character for a typically insular stoic like myself. The doctor entered the room with an air of exasperation about him. Tears streamed down my face. I told him: “I can’t breathe. I think I’m dying.”

And what he did next, I hope, would draw a rally cry from feminists everywhere. He looked up from my chart, rolled his eyes, and said: “You’re probably just anxious. Have you tried calming down?”

World Sepsis Day is held annually on 13 September, and is a perfect opportunity to raise awareness of red flags to look out for. One in five deaths worldwide are associated with sepsis, so why wasn’t it on the doctor’s radar?

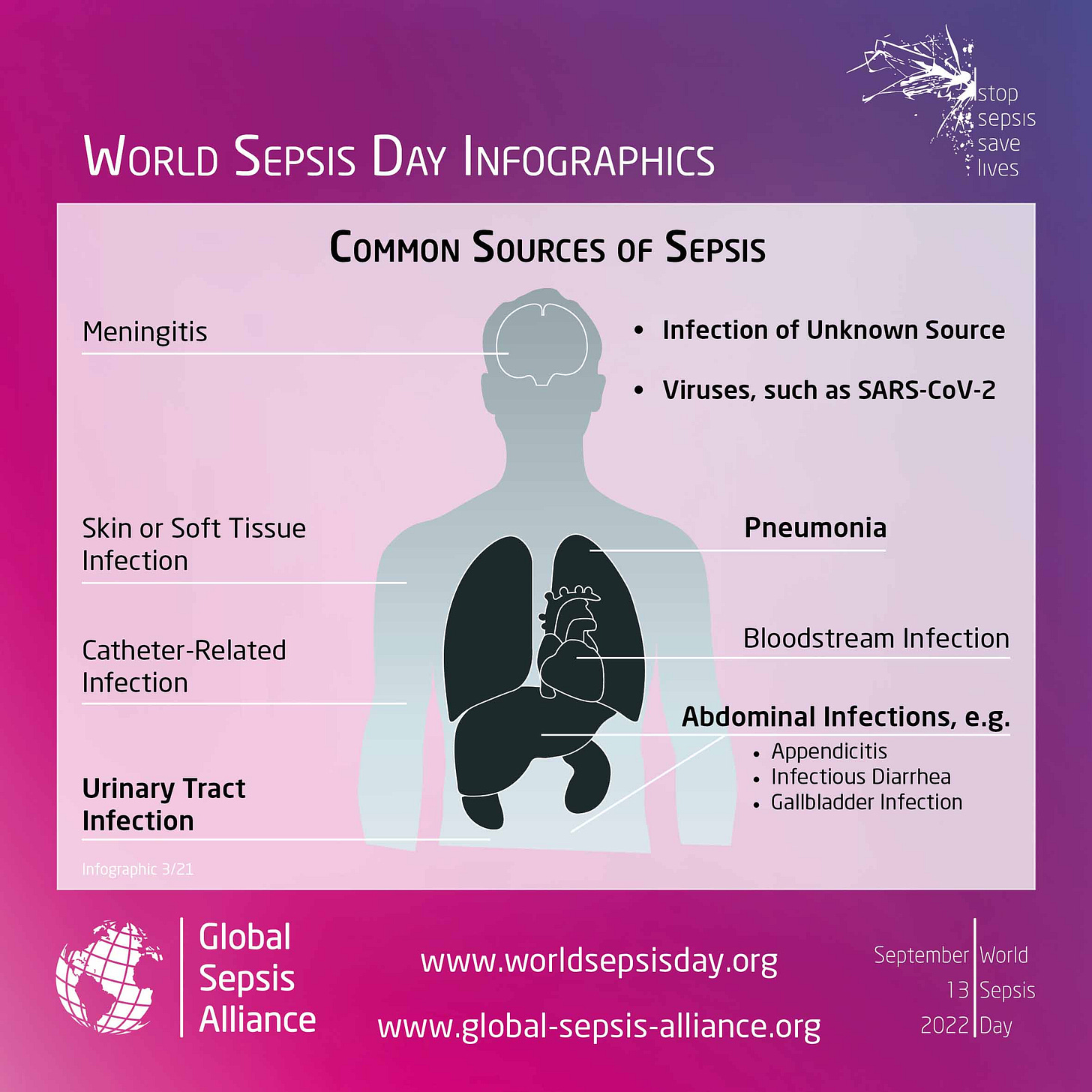

Not to mention, I was beyond high risk. I wish I could say this had been my first brush with death, but after a month spent in hospital, my admission had been a shit-show of missed complications and close calls. Severe ulcerative colitis - a form of inflammatory bowel disease - and a host of other fun co-morbidities led to the removal of my colon, and a stoma formation.

Open surgery? Sepsis risk.

Perforated colon? Sepsis risk.

Multiple infections? Sepsis risk.

Triple immunosuppressed? Sepsis risk.

As a twenty-three-year-old woman, the painful transformation of my body was enough to come to terms with. Throw in a doctor who doesn’t believe you, and the trauma is multiplied.

A recent NY Times article reported on medical gaslighting, and how it disproportionately impacts women, geriatric patients, ethnic minorities, and LGBTQ people. The term originates from the play Gaslight, in which a husband manipulates and tricks his wife with the goal of driving her insane and stealing from her.

In reality, and particularly in the medical sphere, the use of gaslighting tends to be more subtle. For example, your doctor may fail to listen to you, interrupt you frequently, minimise your pain, avoid engaging in discussion, refuse to order certain scans or tests which could rule out important diagnoses, act in a patronising manner, or as per the classic hysterical woman trope: label it all as psychosomatic.

No surprise to my chronically ill pals, I’m sure.

This, combined with lack of awareness of the possible causes, signs, and risks of sepsis, is undoubtedly resulting in countless preventable deaths.

My “anxiety” turned out to be intra-abdominal sepsis, a twisted small intestine, and an abscess under my lungs. Far more structural explanations for my breathlessness, I’d say. And only discovered on begging my own registrar for investigations the following morning, after a night spawned directly from Alfred Hitchcock’s imagination (minus the sexy protagonist).

I required immediate emergency surgery.

When consented, I was advised the risk of death “was not small”, but that death would be a certainty if I wasn’t operated on as soon as possible: an urgency that could’ve been mitigated had the doctor actually listened to me, and applied some basic logic.

I had approximately five minutes to ponder whether I wanted to die, or wanted to maybe die. The maybe triumphed, with little enthusiasm.

In an attempt to combat medical gaslighting, the NY Times lists a number of ways to advocate for yourself, such as keeping detailed records, bringing a list of questions to appointments, or inviting another person for support. My personal favourite is asking for any refusals to be documented in my medical records. It may encourage your doctor to think twice about what they could be missing, or at least open up a franker discussion about their reasoning.

Not that any of this should be necessary.

After all, even for those who make it, the consequences of sepsis can be serious and lifelong. According to the Global Sepsis Alliance, up to 50% of sepsis survivors suffer from lasting physical and/or psychological effects.

They say: “Sepsis, the dysregulated immune system response to infections from bacteria, fungi, or viruses such as COVID-19, affects around 50 million people annually, often leaving survivors with long-term physical consequences, including amputations. Post-sepsis syndrome symptoms are very similar to the ones of the well-known long Covid.”

I’ve personally suffered from chronic fatigue, brain-fog, and PTSD. Short-term, I experienced severe hair loss. Despite the devestation of brushing away clumps of brunette until only a few strands were left, I still consider myself one of the lucky ones.

The Global Sepsis Alliance says it: “rejoices in the results of global advocacy, but the road ahead is still steep, and the number of unnecessary deaths caused by sepsis still too high.”

So, familiarise yourself with the signs. Keep it in that cosy little corner of your brain, ready to whip out at the right moment. Learn how it looks in kids, in adults. Spread the message. Stay vigilant. Given it’s the number one cause of deaths in hospitals, doctors should be more than clued-up on the risks and symptoms. But please don’t rely on that. Your knowledge might just save a life.